Why prices are soaring in the country’s largest grid region, explained in five charts

PJM Interconnection, the nonprofit that manages the country’s largest electricity grid region, is barely known by the general public and almost never mentioned by elected officials–except when something bad happens.

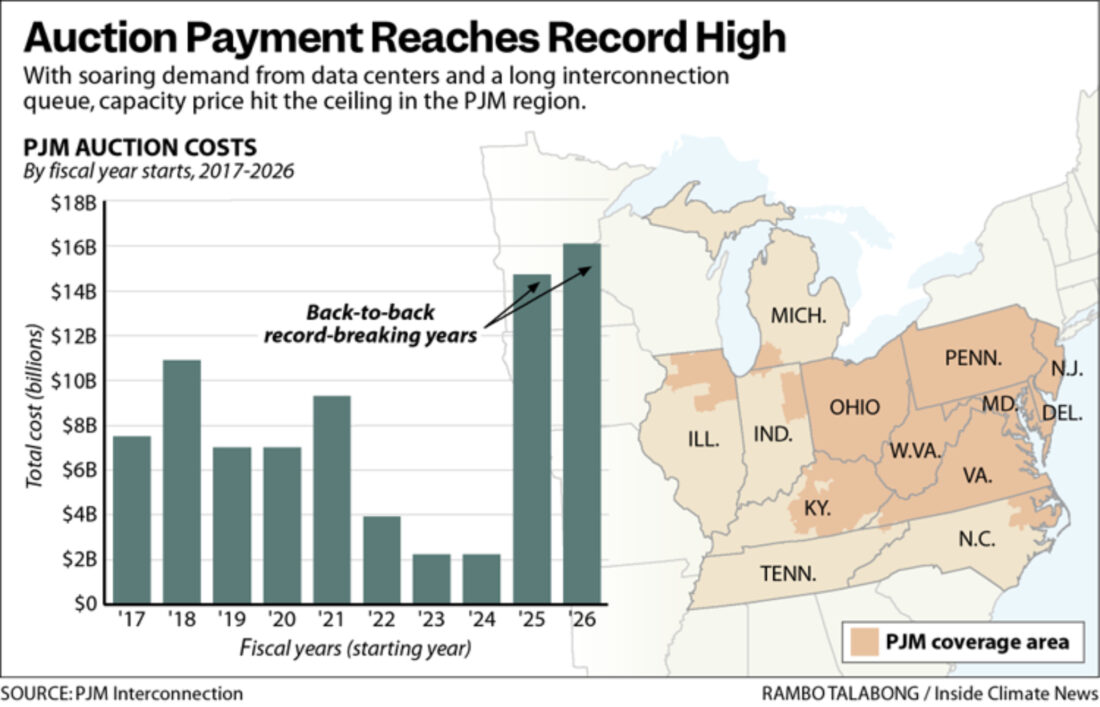

Well, something bad has happened. For two years in a row, PJM’s process for ensuring the grid has sufficient power plant capacity has resulted in record high prices, which will get passed on to consumers. The results are tied to rising electricity demand for data centers and a bottleneck in approving grid connections for new projects.

Almost everything about these events is bound up in layers of complexity.

To explain what’s happening, my colleague Rambo Talabong put together some charts and I spoke with energy policy experts. Together, we aim to make this situation understandable.

PJM, based in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, oversees the grid and electricity markets in a territory that stretches from New Jersey to Chicago. The organization has roots in a 1920s partnership between utilities in Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

“It’s a bunch of utilities who have come together and said, ‘We can provide more reliable, less expensive electric service to customers if we work together and have a mutual aid pact,'” said Abe Silverman, an energy research scholar at Johns Hopkins University who has a background working in utility regulation and the energy industry. “When a customer in New Jersey can buy power from a power plant in New Jersey, or a power plant in Pennsylvania or a power plant in Ohio, it’s going to be cheaper than if they were just buying from power plants from New Jersey.”

One of the ways PJM manages its system is by holding an auction in which power plant owners compete to see who will offer the lowest prices to be available to the grid at all times.

The result is a “capacity price,” which is the price set to ensure that there are enough resources to meet the region’s needs on the hottest days of summer. The price sets the level of payments to participating power plants, which is an important income source for them in addition to what they make from selling electricity.

Last year, the auction produced a result so unusual that this topic, usually reserved for the business press, became general news. The new price, which took effect two months ago, was $269.92 per megawatt-day, an increase from $28.92 per megawatt-day in the previous delivery year.

The most recent auction was last month, yielding an even higher price, $329.17 per megawatt-day. This price will take effect next June.

Since a megawatt-day (which is 24 megawatt-hours) is a unit that most people don’t use or understand, it’s easier to put these results in terms of how many billions of dollars power plant owners stand to receive in aggregate. The change from two years ago is dizzying, going from a low of $2.2 billion to the most recent result of $16.1 billion.

Governors across PJM territory have voiced their displeasure. Maryland Gov. Wes Moore, a Democrat, said, “What PJM has laid out is a slap in the face.”

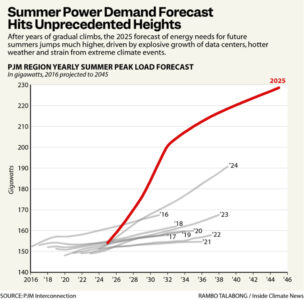

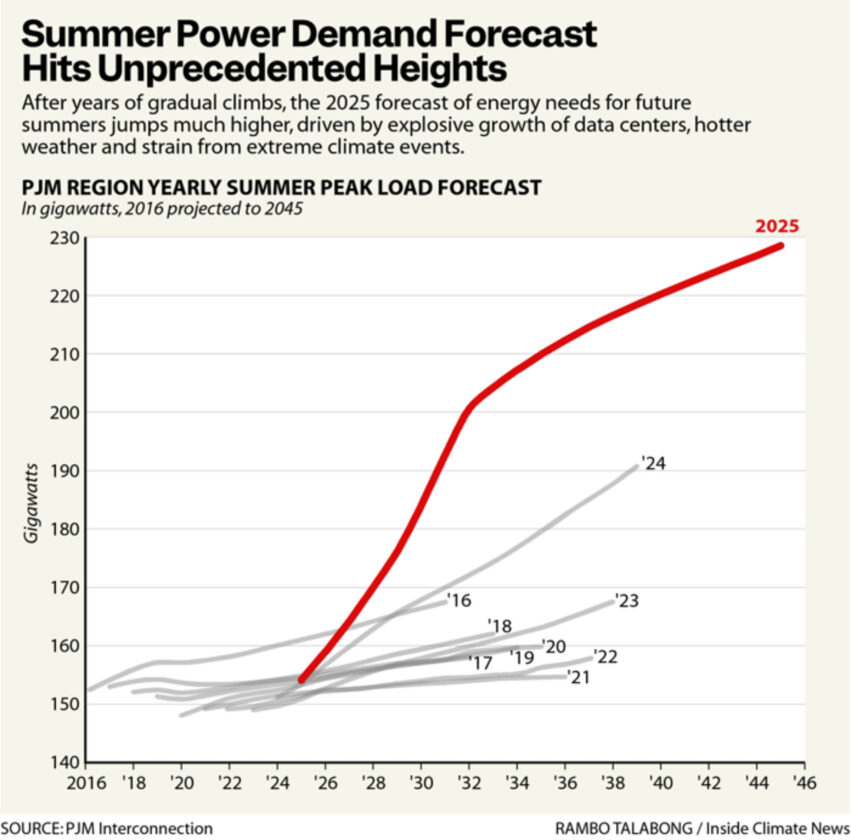

Why did costs go up so much? There are many reasons, but the main one is that electricity demand is soaring, largely due to the development of data centers. The upward curve in PJM’s long-term forecast is in contrast to the prior decade-plus of flat growth.

“Supply and demand,” said Daniel Lockwood, a PJM spokesman, when asked about the reasons for rising costs. “Unprecedented and continuing growth in demand from the proliferation of high-demand data centers in the region.”

Silverman from Johns Hopkins agreed that this is, by far, the leading factor.

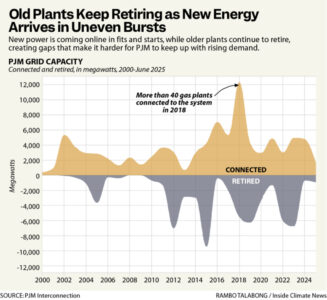

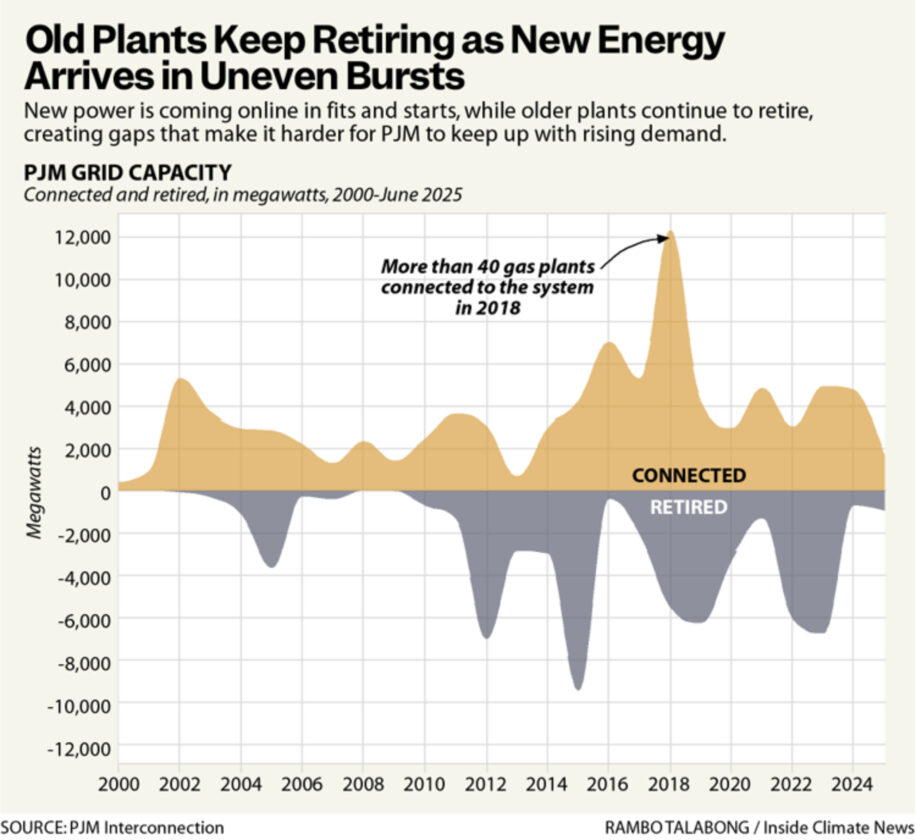

When demand is flat, old and inefficient power plants often struggle to compete, leading plant owners to close the plants that are losing money or barely profitable. Since 2000, PJM has seen a shift as coal-fired power plants reached the end of their lives and were replaced by natural gas plants and some renewables.

The retirement of old coal plants was good for the environment, but the rapid loss of those plants has helped to intensify the supply crunch that’s now happening.

But plant retirements are only part of the picture.

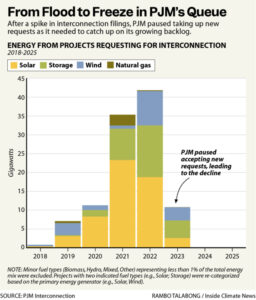

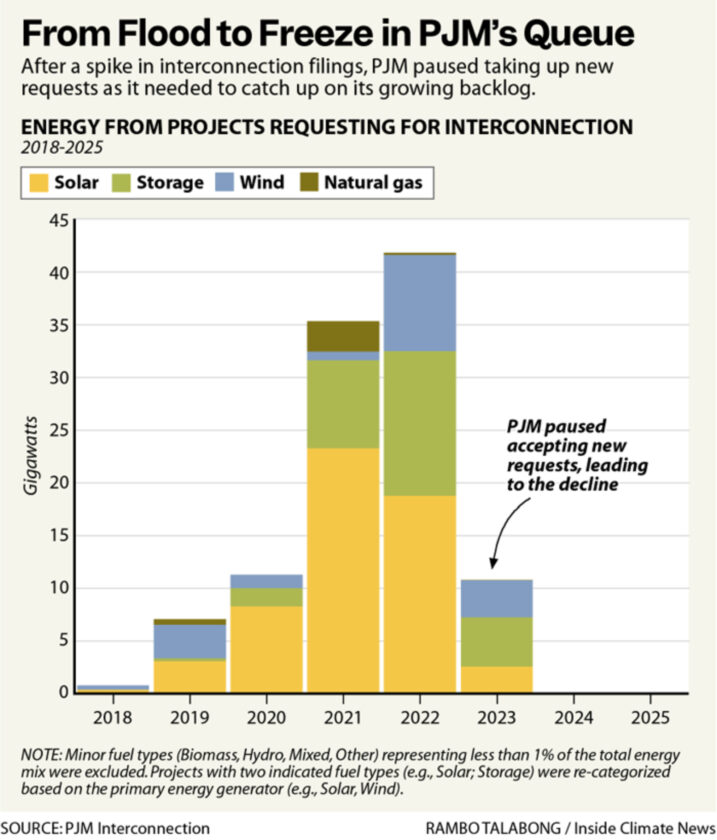

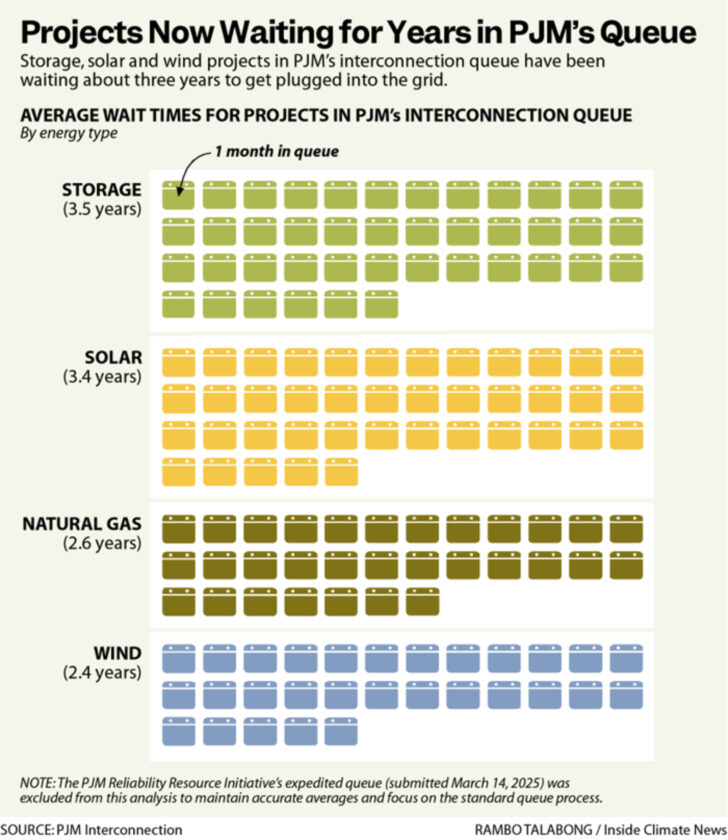

One of the reasons PJM is struggling to secure enough power plant capacity is the organization’s challenges in connecting new plants to the grid.

PJM has an online queue in which owners of prospective power plants get in line to gain approval to hook up to interstate power lines. Ideally, this would be a fast process, but the queue has turned into a quagmire of long waits, meaning the grid isn’t getting some of the new power plants that would otherwise be ready.

Most of the affected projects are solar arrays, the results of a solar boom across much of PJM territory.

Some caveats: Some of the projects in the queue are highly speculative and unlikely to get built, so the numbers can be misleading. Also, some projects are held back by more than just PJM, with challenges getting local permits and other factors.

As of June, there were 63 gigawatts of projects waiting in PJM’s interconnection process that should be completed by the end of 2026, according to Lockwood, the PJM spokesman. He noted that there are 46 gigawatts of projects that have agreements to plug into the grid today, but some aren’t being built because of factors beyond PJM’s control, such as siting, permitting and financing.

Clean energy and consumer advocates have said PJM often acts as an obstacle to reducing dependence on fossil fuels.

“The power grid operator’s policy decisions too often favor outdated, expensive power plants and needlessly block low-cost clean energy resources and battery projects from connecting to the grid and bringing down prices,” said Sarah Moskowitz, executive director of the Citizens Utility Board of Illinois, in a statement. “This extended price spike was preventable.”

So, how much is a household’s electricity bill rising because of all this?

I asked several of the largest utilities in PJM for specifics. Their answers had wide variations, which helps to show differences in rate structures, state regulations and other factors that affect how and when the PJM charges reach consumers.

PSEG, the largest utility in New Jersey, notified customers in February of an impending 17 percent rate increase that was largely due to the rise in PJM charges. As of June, a household using 650 kilowatt-hours per month now paid $183, which was $27 more than before.

ComEd, which serves the Chicago area, has increased its residential bills by roughly 10 percent because of the surge in PJM charges that took effect in June. A typical household, which uses 609 kilowatt-hours per month, is paying $117, which is $11 more than before.

Dominion, which is the largest utility in Virginia and also has PJM customers in North Carolina, said its customers were largely insulated from PJM costs because the company gets most of its electricity from power plants that it owns. This is different from most large utilities in PJM, which do not directly own power plants and use market-based systems to obtain electricity for customers.

The total monthly cost for PJM capacity, even after the increase, would be less than $2 per month, according to a Dominion spokesman.

Just like PJM’s capacity prices have gone up, they can come back down. But for that to happen, some of the market fundamentals will need to change. I don’t expect that to happen any time soon.

So you’re probably going to keep hearing about PJM in the context of explanations for high electricity prices.

——

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment.

——

Pennsylvania Capital-Star is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Pennsylvania Capital-Star maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Tim Lambert for questions: info@penncapital-star.com. Follow Pennsylvania Capital-Star on Facebook and Twitter.